DVD REVIEW

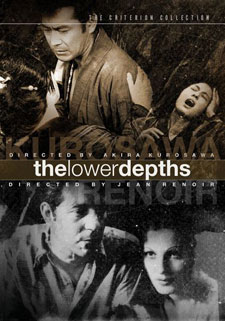

Jean Renoir's The Lower Depths (Les Bas-fonds) Year: 1936. Running time: 85 minutes. Black and white. Directed by Jean Renoir. Based on the play by Maxim Gorky. Stars Jean Gabin and Louis Jouvet. Aspect ratio: 1.33:1. In French with optional English subtitles. DVD release by The Criterion Collection. Akira Kurosawa's The Lower Depths (Donzoko) Year: 1957. Running time: 125 minutes. Black and white. Directed by Akira Kurosawa. Based on the play by Maxim Gorky. Stars Toshiro Mifune, Isuzu Yamada, and Minoru Chiaki. Aspect ratio: 1.33:1. In Japanese with optional English subtitles. DVD release The Criterion Collection. Review by David Gurevich “Maxim Gorky was a great proletarian writer and the founder of Socialist Realism." For sixty years, millions of high-school students in the Soviet Union wrote this phrase to open their essays. This was inevitably followed by a long reflective pause. What the hell else can I say about the old buzzard?

The Soviet Union is no more, of course, and Internet is. There is a connection between the two facts, which I won't go into here, but in reference to the above I should say that just as Gorky's work is no longer a must theme for high-school essays, those wishing to choose it can easily download a slew of ready-made essays from Internet. No more staring at the blank page.

Gorky himself is a figure tragic enough. His talent won him considerable celebrity even before the Revolution, though many would reason, with some merit, that his rise was politically motivated and promoted by the bleeding-heart arbiters of public taste. Not only was he the first to fill the pages with descriptions of drunken bums and noble tramps, but he came up from their ranks himself: after his parents died, he was thrown out of the house by his own grandfather and had to hit the road. When he started writing, every editor-intellectual was charmed immediately: the kid had what we call street cred.

The whole story of how from a celebrity (they had champagne and groupies in 1902, too) Gorky became a Bolshevik and subsequently the first Chairman of the Writers' Union, of his disillusionment with Bolshevism he had to keep secret and the turning of his vibrant prose into the deadwood of the Socialist era is a staple of Russian Lit courses. Suffice it to say that even in those days his celebrity traveled well, and much of his work in theater became known outside Russia, including his best-known play The Lower Depths. (The original Russian version is titled Na Dne or At the Bottom; the English version is, while technically correct, a tad more ponderous and, alas, loses the brilliant five-letter terseness of the original. Such are the wages of translation.)

As a play, The Lower Depths is simple enough: its main character is its location, a flophouse where bums from all walks of society end up. They spend most of the time drinking, gambling, and plotting against one another, but mostly just attacking one another's dreams and aspirations. The moment one of them gets misty-eyed either about his shiny past or his improbable future, he/she is instantly knocked down by the rest, long before he/she gets a chance to get maudlin. This goes on for four acts, with some of the characters dying, others getting arrested, and yet others killing themselves. The only feeble stab at a plot comes via the noirish story of the elderly flophouse owner, his young wife, and virile Pepel the Thief. For details, see The Postman Always Rings Twice, with the only addition being that Pepel also falls in love with the wife's kid sister. Viewed through the modern lens, the piece is quasi-archaic and serves as a good illustration of the transience of literature chained to social issues of the day. Today, I don't think even Mike Nichols could score with this one on Broadway.

Besides shocking society with stories of his bums, Gorky had an agenda of his own. Like many others who rose from the bottom, he became a fanatical anti-cleric. (When he became a Bolshevik, he simply applied his fanaticism to a different religion). Accordingly, he introduces Luka, a religious pilgrim who consoles other characters with stories of their goodness being rewarded in the next world. To those who protest, he says, "Truth is too harsh for a man in this world." (Or, translated into Broadway-Hollywood lingo, "YOU CAN'T HANDLE THE TRUTH!") Remarkably, both Jack Nicholson's marine colonel and Gorky's Luka get their comeuppance; in 90 years, little has changed in the world of liberal clichés.

Thirty-five years after its premiere this rather simple-minded story caught the eye of Jean Renoir, already one of the most famous French directors. This is striking only at first glance: Popular Front was running French arts (far more tightly than Hollywood actors' unions later would) and felt a desperate need to show their Socialist sympathies. Gorky's play fit the bill. Renoir came aboard. The result is a resounding failure, and a revealing one—the kind of play Gorky would be forced to write under the Party pressure at the time. The 1902 original is a dark, hopeless denunciation of capitalism; in 1936, the flower of Socialism was in full bloom, and the characters had to be shown a way out of their misery. The orthodox Soviet writers had to apply Socialist-Realist aesthetic criteria to their own work; but Soviet directors, however Orthodox, were too conservative to treat the classics, Gorky included, with anything less than awe and would not dare to "improve" on them a la Renoir.

The original takes place strictly within the dark, oppressive flophouse (with one scene at the abandoned lot); Renoir takes the action out to ritzy society nightclubs and sunlit French countryside, where his lovebirds finally escape (in the original, they just disappear, presumably hauled off to jail). Forget about Luka the pilgrim; here, center stage is taken by Baron (Louis Jouvet), a degenerate gambler, who loses his fortune in the casino and ends up as another flophouse denizen, and Pepel the Thief. If Gorky romanticizes Pepel, Renoir worships the ground under his feet: he casts Jean Gabin, the biggest future French film star, in the part. (No Hollywood director/producer worships a criminal like a Socialist-minded director does.) The two meet cute—Pepel comes to rob Baron's mansion, which has already been cleaned out by creditors—and strike a friendship a la much later Delon-Belmondo movies. Also, Renoir makes the most of the noirish love triangle, or, rather, quadrangle—Pepel and the landlord couple and their sister. The result is unbearable to watch, especially the scenes where the poor Natasha, the landlady's sister, is being pushed to marry a high-ranking policeman. The virtue has never been assaulted with so much brutality and so little credibility. On top of everything else, there's the acting: with his authentic blue-collar masculinity, Gabin does not do much besides menacingly roll his jowls and light up one Gaulouise after another; but Junie Astor, his love interest, had been foisted upon Renoir by the producer, and was so wooden that Renoir had to shoot mostly around her. The latter circumstance (mentioned in the enclosed notes for The Criterion Collection's DVD release of The Lower Depths) makes you sit up: It could have been worse?

Although slicing up the play radically, Renoir kept the Russian names and the Czarist period. In 1957, Akira Kurosawa, the late great maître of Japanese cinema, took the opposite tack: he stuck faithfully to the original but moved the setting to mid-19th-century Japan and livened up the oppressive interiors by using contemporary music. The result is mixed: while the main characters and plot are intact (Toshiro Mifune can more than hold his own against Gabin), the supporting cast—the alcoholic actor, the impoverished gambling samurai, and the candy vendor—act as a Greek chorus of sorts, drinking merrily and dropping witty barbs at life in general. The anti-clerical theme is still there, but now it is aimed at organized religion—Buddhist monks; thus it loses Gorky's stridency and, with Bokuzen Hidari's virtuoso performance as the pilgrim, becomes more humane. The black-and-white interiors, all rot and rags, are a faithful reproduction of an Edo era settlement, but they are shot in a stark Expressionist fashion, which enhances the feeling of desolation, yet makes it appear more of a human condition, rather than the stale us-against-them message. And the grand finale is absolutely stunning: with the main characters gone, mostly to jail, the above-mentioned chorus gets drunk and goes into a long wonderful improvisational musical number, and you don't need to know that this is a musical form called bakabayashi (literally, "fools' orchestra"), a popular Shinto shrine festivity of the period (as the DVD's notes helpfully explain), to see that even here, at the bottom of society, people can still enjoy life and retain their humanity—all until the news arrives of the actor's suicide. "That was such a great party," the gambler says. "Then he had to go and ruin everything." Kurosawa took a dated, mediocre play and made it both modern and alive.

Jean Renoir's The Lower Depths (Les Bas-fonds, 1936) and Akira Kurosawa's The Lower Depths (Donzoko, 1957) are both now available on DVD from The Criterion Collection in high-definition digital transfers with restored image and sound. Jean Renoir's The Lower Depths special feature: introduction to the film by Jean Renoir. Ikira Kurosawa's The Lower Depths special features:

a documentary on the making of The Lower Depths, part of the Toho Masterworks series Akira Kurosawa: It Is Wonderful to Create; audio commentary featuring Japanese-film expert Donald Richie (A Hundred Years of Japanese Film); new and improved English subtitle translation by renowned Japanese-film translator Linda Hoaglund; cast biographies by Stephen Prince (The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa); and an original theatrical trailer. Suggested retail price: $39.95. For more information, check out the Criterion Collection Web site.

|