|

Upon listening to the album, we didn't quite understand that the music revisited the more dynamic and problematic race-rebel issues of early rock. "Wrong 'em Boyo" was a ska-take on the traditional jump blues Stagger Lee narrative, and "Brand New Cadillac" was a rocked-up twelve-bar Muddy Waters-style tune; all we knew was that frontman Joe Strummer sounded raspy and impassioned through his cockney accent, and a lot of the songs sped up as they went along. We didn't have an erudite insider knowledge of the references The Clash made, but we knew this music rocked with a sense of authenticity. We could feel the black holes opening up to something like history in the music, could see it in the album cover. Suddenly the narcissistic present-only of adolescence we felt in Poison and Quiet Riot was outweighed. Punk made us nostalgic in advance for some unspecific history that wasn't even ours.

It was this weight, the iconography of nostalgia, that had allowed the Clash, as opposed to the other ground-zero Britpunk band, the Sex Pistols, to solidify punk as a historical development in music. By the time of London Calling, the band was only four years into its career, but already obsessed with time travel. For the kind of suburban kids who bought Clash albums and waited patiently for the infuriatingly Michael Jackson-oriented MTV to play Clash videos, late twentieth century British subcultural history was a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. What were punks? What did they do? The Clash mirrored our questions with their own. "What was reggae and ska?" they asked. "And what is the Babylon the Rastas rebel against? Remember when we were Rockers and fought with Mods and Teddy Boys? What sense can we make of authentic American Rock? What are our working-class roots? Um, what kind of haircuts should we get?"

This last question, seemingly the most trivial, turned out to be important, capable of containing most of the others. In the 1970s, The Clash had followed the stylistic lead of the Sex Pistols, who had followed the quick-to-burn-out American proto-punk Richard Hell in cutting their own hair into a spiky mess. As the anarchic excess of the Pistols blew them into smithereens in 1978, however, and the Clash found their career miraculously surviving into the '80s, the band began to cultivate a look of hard-working perseverance, re-adopting the Rocker ducks-asses they had jettisoned in becoming punks. Over the next few years, the sidewalls of Joe Strummer's greasy quiff would get shorter and shorter until, by 1982 and the video shoots for the singles off Combat Rock, he would finally give in to what was already the most cliche of punk images--the mohawk. This last question, seemingly the most trivial, turned out to be important, capable of containing most of the others. In the 1970s, The Clash had followed the stylistic lead of the Sex Pistols, who had followed the quick-to-burn-out American proto-punk Richard Hell in cutting their own hair into a spiky mess. As the anarchic excess of the Pistols blew them into smithereens in 1978, however, and the Clash found their career miraculously surviving into the '80s, the band began to cultivate a look of hard-working perseverance, re-adopting the Rocker ducks-asses they had jettisoned in becoming punks. Over the next few years, the sidewalls of Joe Strummer's greasy quiff would get shorter and shorter until, by 1982 and the video shoots for the singles off Combat Rock, he would finally give in to what was already the most cliche of punk images--the mohawk.

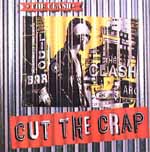

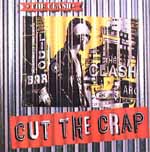

By 1985, a mohawk on a Strummer-like figure would grace the cover of Cut the Crap, the band's last album. Significantly, the 'do coincided with the success of Combat Rock, the band's biggest seller. "Should I Stay or Should I Go?" and "Rock the Casbah" would become radio staples off Combat Rock, and the videos for these songs would spend the year in heavy rotation on MTV. Middle American rural, and suburban kids with no access to a local punk culture could zero in, through the camera's loving gaze on Strummer's mohawk, on the one thing on the screen they were sure was capital-P punk. The band's various flirtations with cultural and subcultural styles from different eras--brothel creepers, porkpie hats, Maoist revolutionary garb, and combat gear--were confusing, and led to serious and often contradictory questions about punk's historical roots and political leanings. The mohawk summed all that up and defined the subculture as if in dress rehearsal for a history test: this is how you know it's punk. By 1985, a mohawk on a Strummer-like figure would grace the cover of Cut the Crap, the band's last album. Significantly, the 'do coincided with the success of Combat Rock, the band's biggest seller. "Should I Stay or Should I Go?" and "Rock the Casbah" would become radio staples off Combat Rock, and the videos for these songs would spend the year in heavy rotation on MTV. Middle American rural, and suburban kids with no access to a local punk culture could zero in, through the camera's loving gaze on Strummer's mohawk, on the one thing on the screen they were sure was capital-P punk. The band's various flirtations with cultural and subcultural styles from different eras--brothel creepers, porkpie hats, Maoist revolutionary garb, and combat gear--were confusing, and led to serious and often contradictory questions about punk's historical roots and political leanings. The mohawk summed all that up and defined the subculture as if in dress rehearsal for a history test: this is how you know it's punk.

The nostalgia in Strummer's iconic self-definition was due not only to the commercial demands of having become a superstar but was also due to the fact that punk had, even before the turn of the decade, also been historicized for the outside world. Dick Hebdige, in his 1979 cornerstone work of Birmingham-school British cultural studies Subculture: The Meaning of Style, had, before anyone knew that any part of the movement would survive the '70s, thoroughly academicized punk style. In a remarkably thorough dissection of clothes, hair, behavior, and music, Hebdige institutionalized punk as living history with seemingly solid but dizzyingly diverse historical connections to British (and world) socioeconomics, racial identity, politics, and culture. To Hebdige, for example, a mohawk was analogous to Rasta dreadlocks, safety-pinned jackets and clothing were postmodern alternatives to consumer culture, and styles of dance were performances of working-class solidarity. In a cultural climate that could produce such historical and sociological fixing of a stylistic system, how could any new punk production of meaning be anything but a reproduction? The Clash's move deeper into styles and themes of the past (increased Maoist sloganeering, American rock and blues, an album of Jamaican dub versions of their songs entitled Super Black Market Clash) was integral to their success. If the cause of their nostalgia was a retreat from the milieu of mainstream criticism, the effect was streamlined "genre identification," a heightened awareness of punk's connectedness within popular culture, and more and more circular reference to its very "punkness."

Just four years after Combat Rock, with "Rock the Casbah" and "Should I Stay or Should I Go" still firmly ensconced in the radio consciousness of the Western World, Greil Marcus went Hebdige one better. His book Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century used the punk events between 1976 and 1979 as the touchstone for his ambitious title. Lipstick Traces places the full weight of the history of the twentieth century intellectual avant-garde squarely on the shoulders of punk. For Hebdige, punk was emblematic of particular sociocultural moment in history; for Marcus, punk was emblematic of the nature of twentieth-century history itself. All of this scholarship romanticizes the idea of punk as a kind of living history that is not only historically interesting but necessary to subvert, from within, what is constructed as a creeping fascism of government in league with consumer culture.

page 1 of 2

|

So when we came across London Calling, the already four-year-old album by seminal punks The Clash, we put aside the pile of Van Halen and Led Zeppelin albums we had earmarked for surreptitious recording.

So when we came across London Calling, the already four-year-old album by seminal punks The Clash, we put aside the pile of Van Halen and Led Zeppelin albums we had earmarked for surreptitious recording.

Where heavy metal albums had neo-Gothic typescript with gratuitous umlauts, London Calling featured pink and green '50s diner lettering; where heavy metal albums came with posed color group shots of the band wearing eye makeup and ratted hair, London Calling had a blurry black-and-white documentary photo in which Simonon's face wasn't even visible. Where heavy metal evoked glamour, this image evoked a sincerity that transcended the quaint patina of the fifties rock we dismissed as tame. Like Chris, it was as unsettling as it was cool.

Where heavy metal albums had neo-Gothic typescript with gratuitous umlauts, London Calling featured pink and green '50s diner lettering; where heavy metal albums came with posed color group shots of the band wearing eye makeup and ratted hair, London Calling had a blurry black-and-white documentary photo in which Simonon's face wasn't even visible. Where heavy metal evoked glamour, this image evoked a sincerity that transcended the quaint patina of the fifties rock we dismissed as tame. Like Chris, it was as unsettling as it was cool.

This last question, seemingly the most trivial, turned out to be important, capable of containing most of the others. In the 1970s, The Clash had followed the stylistic lead of the Sex Pistols, who had followed the quick-to-burn-out American proto-punk Richard Hell in cutting their own hair into a spiky mess. As the anarchic excess of the Pistols blew them into smithereens in 1978, however, and the Clash found their career miraculously surviving into the '80s, the band began to cultivate a look of hard-working perseverance, re-adopting the Rocker ducks-asses they had jettisoned in becoming punks. Over the next few years, the sidewalls of Joe Strummer's greasy quiff would get shorter and shorter until, by 1982 and the video shoots for the singles off Combat Rock, he would finally give in to what was already the most cliche of punk images--the mohawk.

This last question, seemingly the most trivial, turned out to be important, capable of containing most of the others. In the 1970s, The Clash had followed the stylistic lead of the Sex Pistols, who had followed the quick-to-burn-out American proto-punk Richard Hell in cutting their own hair into a spiky mess. As the anarchic excess of the Pistols blew them into smithereens in 1978, however, and the Clash found their career miraculously surviving into the '80s, the band began to cultivate a look of hard-working perseverance, re-adopting the Rocker ducks-asses they had jettisoned in becoming punks. Over the next few years, the sidewalls of Joe Strummer's greasy quiff would get shorter and shorter until, by 1982 and the video shoots for the singles off Combat Rock, he would finally give in to what was already the most cliche of punk images--the mohawk.

By 1985, a mohawk on a Strummer-like figure would grace the cover of Cut the Crap, the band's last album. Significantly, the 'do coincided with the success of Combat Rock, the band's biggest seller. "Should I Stay or Should I Go?" and "Rock the Casbah" would become radio staples off Combat Rock, and the videos for these songs would spend the year in heavy rotation on MTV. Middle American rural, and suburban kids with no access to a local punk culture could zero in, through the camera's loving gaze on Strummer's mohawk, on the one thing on the screen they were sure was capital-P punk. The band's various flirtations with cultural and subcultural styles from different eras--brothel creepers, porkpie hats, Maoist revolutionary garb, and combat gear--were confusing, and led to serious and often contradictory questions about punk's historical roots and political leanings. The mohawk summed all that up and defined the subculture as if in dress rehearsal for a history test: this is how you know it's punk.

By 1985, a mohawk on a Strummer-like figure would grace the cover of Cut the Crap, the band's last album. Significantly, the 'do coincided with the success of Combat Rock, the band's biggest seller. "Should I Stay or Should I Go?" and "Rock the Casbah" would become radio staples off Combat Rock, and the videos for these songs would spend the year in heavy rotation on MTV. Middle American rural, and suburban kids with no access to a local punk culture could zero in, through the camera's loving gaze on Strummer's mohawk, on the one thing on the screen they were sure was capital-P punk. The band's various flirtations with cultural and subcultural styles from different eras--brothel creepers, porkpie hats, Maoist revolutionary garb, and combat gear--were confusing, and led to serious and often contradictory questions about punk's historical roots and political leanings. The mohawk summed all that up and defined the subculture as if in dress rehearsal for a history test: this is how you know it's punk.