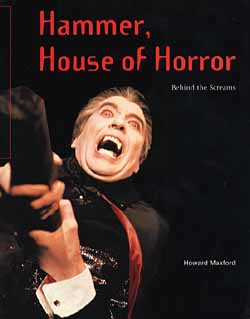

However in December 1996, Overlook Press released a third book in the Hammer onslaught, Hammer, House of Horror by Howard Maxford, at a considerably slimmer 192 pages and a much affordable price tag of $27.95. In addition, Hammer, House of Horror is arguably the best designed book of the group, featuring 20 full-color and 57 black-and-white photographs on high-quality paper.

Among the intriguing photographs, you'll find Peter Cushing collecting a severed head in The Curse of Frankenstein (a shot deleted from the final print of the movie) and Yutte Stensgaard with fangs showing and blood running over her nearly-nude chest (a famous publicity still with no corresponding camera shot in the movie) in Lust for a Vampire. Hammer, House of Horror is a handsome and professionally-designed book that contains a wealth of valuable information and photographs. However, when the text addresses the movies themselves, the book disappoints.

Peter Cushing tinkers with a severed head in The Curse of Frankenstein.

Peter Cushing tinkers with a severed head in The Curse of Frankenstein.

Author Howard Maxford attempts to tackle the entire history of Hammer, from the studio's early genesis in the '30s through its "last gasps" in the late '70s. However, he rarely provides many insights into the filmmaking. His descriptions of director Terence Fisher's contributions, for example, are usually contained to "directorial flourishes abound," "perfectly visualized," and "keeps the action moving." Or when he finds the movies lacking then the direction "lacks pace." But Maxford doesn't probe very far beyond such surface analysis. As a result, someone can read this entire book without really finding out anything about Fisher's directorial style. And that's a shame.

Fisher was one of the great directors of gothic horror, taking the helm in Dracula, The Curse of Frankenstein, The Mummy, The Brides of Dracula, and many others. He captured a palpable sense of burgeoning decadence, using liberal doses of bright reds and muted yellows and browns. His films unrolled like huge ornate Victorian tapestries, filled with dust and forbidden desires. But Maxford fails to convey these crucial contributions of Fisher.

Christopher Lee collecting a little blood from Caroline Munro in Dracula A.D. 1972.

Christopher Lee collecting a little blood from Caroline Munro in Dracula A.D. 1972.

Likewise, other aspects of filmmaking get a similar superficial treatment: "performances are fine," "setting is made the most of," the director "adds immeasurably," and actors are "top notch." This type of quick judgmental quip is tolerable in small doses, as long as it alternates with some more probing analysis, but Maxford uses this approach extensively. If he had given us an in-depth study of the history of Hammer and provided an inside perspective on the studio's rise and fall, with interviews with actors and filmmakers, this type of analysis of the films themselves might have been acceptable, but Maxford confines himself almost exclusively to this type of superficial account of the Hammer product.

Still, the book is not without its value. In particular, I'm sure I'll be returning to the book's "Hammer - Who's Who" often, as well as to the chronology and filmography. These sections make it much easier to trace the contributions of frequent Hammer actors and filmmakers, such as Barbara Shelley (one of Hammer's best female performers), Freddie Francis (the great photographer and unfortunately weak director), Roy Ashton (Hammer's main make-up artist), James Bernard (a frequent composer), Bernard Robinson (the man responsible for the art direction on most of Hammer's best films), and many others.

Yutte Stensgaard in a famous publicity still from Lust for a Vampire.

Yutte Stensgaard in a famous publicity still from Lust for a Vampire.

On occasion, Maxford also provides some fascinating insights into the production history of the films. For example, he reveals that Hammer's version of Phantom of the Opera was scripted when Cary Grant (!) was considering playing the Phantom. And after Grant pulled out of the project, Hammer was left with a script tailored for Grant's romantic screen image and without any comparable replacements. (Herbert Lom would eventually take the role.) Maxford also charts Hammer's tendency to shoot films back to back so that new sets could be used at least twice, as when Dracula's castle in Dracula--Prince of Darkness was redressed to resemble a Russian winter palace in Rasputin--The Mad Monk.

Overall, however, Hammer, House of Horror comes as a let down. It's filled with uninspired writing that only occasionally offers any insights into the history of one of the most fascinating movie studios in the history of horror cinema.

Hammer, House of Horror by Howard Maxford, The Overlook Press, $27.95, hardcover.