Hitchcock plays a similar game with his audience in Psycho (1960). At

first we, along with Marian, Arbogast, Sam and Lila, think that Mrs.

Bates is alive and living in the Bates home. Hitchcock toys with us by

suggesting a reality to Mrs. Bates through the use of a voice over and a

vertiginious camera angle as Norman carries his mother down to the fruit

cellar.

Next, we are given the Sheriff and his wife's version of

reality: Norman's mother died ten years earlier as the result of a

homicide/suicide with her lover. Finally, after Lila's investigation of

the Bates home, we "discover" the "real" reality: Norman killed his

mother and her lover but kept his mother's corpse around the house to

preserve her memory.

Next, we are given the Sheriff and his wife's version of

reality: Norman's mother died ten years earlier as the result of a

homicide/suicide with her lover. Finally, after Lila's investigation of

the Bates home, we "discover" the "real" reality: Norman killed his

mother and her lover but kept his mother's corpse around the house to

preserve her memory.

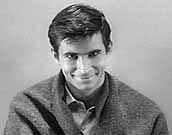

The final shots of the film, showing Norman

completely transformed into "mother," suggest another, deeper still

reality to the film. These shifting levels of reality suggest to us why

Hitchcock thought of Psycho as a "fun" picture—this film that is

largely concerned with the theme of voyeurism is an elaborate game of

discovering what is real and what is illusion.

The last shot, as Norman

(mother) grins into the camera, suggest we have had a delightful black

joke played upon us; but it is a joke that audiences apparently loved,

given that Psycho was Hitchcock's most commercially successful film.

The last shot, as Norman

(mother) grins into the camera, suggest we have had a delightful black

joke played upon us; but it is a joke that audiences apparently loved,

given that Psycho was Hitchcock's most commercially successful film.