video series review by Gary Morris -- page 2 of 2 | |

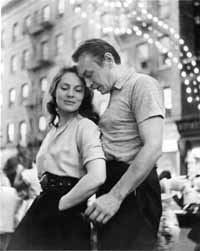

Gerald O'Loughlin and Cathy Dunn in Lovers and Lollipops. (©1997 |

In spite of the commercial and critical success of Little Fugitive (which plays frequently on AMC these days), the filmmakers had trouble getting financing for their next work but somehow managed. Anyone who saw Little Fugitive would recognize Lovers and Lollipops (1955) as the work of the same team, even without the credits. Again we see the milieu of New York, rendered in gorgeous black-and-white compositions, and again we see a child at the center. This time it’s a girl, Peggy (Cathy Dunn), who recalls Joey Norton in her tenacity and willfulness. Both are imaginative kids with an active inner life who can entertain themselves and are well-equipped to deal with any adults who get in the way of their fun. Joey had no visible father, only brief, shadowy substitutes like the pony-ride man; Peggy’s father is dead, and she feels compelled to resist her mother Ann’s (Lori March) threat to replace him with a new one in the form of Larry (Gerald O’Louglin), an old friend who’s visiting. The story is a strange, alternately sweet and sad triangle—Ann and Larry’s precarious relationship and Peggy’s simultaneous attempts to thwart it and find her place in it. In Little Fugitive, Joey’s interactions were mostly brief encounters with strangers on the beach. Lovers and Lollipops focuses closely on Peggy’s relationships with the adults in her life—her mother, Larry, a sarcastic babysitter, and a photographer who’s taking pictures of her for a book. In the process of coming to grips with her mother’s romantic life, she torments the indulgent Larry in the guise of spending "quality time" with him. During a scene where he reads to her, she crawls all over him, mimics and laughs at him, and interrupts him. This is a rehearsal for other, more cutting scenes where she causes endless grief by hiding from him in a parking lot (later she complains to her mother, "he lost me too!"). |

Any attempt at romance by Ann and Larry is usually met with force by Peggy, who eventually offers a litany of his "crimes" in the martyred mode of a child: "He gave me a rotten sandwich and made me eat all of it!" Peggy’s convention-busting is at once enchanting and nerve-wracking; it filigrees the film, most notably in a scene where she insists on carrying her toy sailboat into a museum rather than checking it. She sneaks it in and sails it on one of the museum’s small pools, creating a poignant symbol of her own potential drifting away from her mother.

Any attempt at romance by Ann and Larry is usually met with force by Peggy, who eventually offers a litany of his "crimes" in the martyred mode of a child: "He gave me a rotten sandwich and made me eat all of it!" Peggy’s convention-busting is at once enchanting and nerve-wracking; it filigrees the film, most notably in a scene where she insists on carrying her toy sailboat into a museum rather than checking it. She sneaks it in and sails it on one of the museum’s small pools, creating a poignant symbol of her own potential drifting away from her mother.