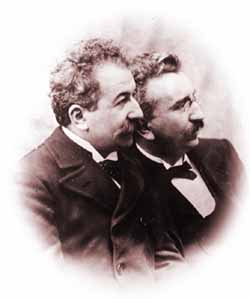

The Lumières saw their invention with the eyes of entrepreneurs and soon opened a theater for exhibiting their films. Lines stretched down the block. Audiences were enthralled. Soon the Lumières trained additional cameramen and sent them on missions around the world. Lumière camera operators ventured to Mexico, Russia, Australia, Japan, and most points in between. In fact, the only continent that they did not step foot upon was Antarctica.

Bertrand Tavernier clearly loves the Lumière films. He isn't just a hired narrator. He knows the history of the Lumières and he's able to provide many insightful comments. One of the most surprising aspects of the video is the way that Tavernier illuminates how the Lumières actually shaped their films. The Lumières weren't merely recording life on the street; they were making decisions about how to best present images on film. Rarely do you find a static, full frontal view, for example: the Lumières always looked for the diagonal as a way to reinforce the illusion of depth. Louis Lumière was an experienced photographer and he brought a fine sense of composition to his work with the motion picture camera. In later years, he claimed that the films were made to simply "reproduce life." And many critics have pointed to these films as part of a realistic tradition--in contrast to the fantastic works of Georges Melies. However, as Tavernier points out, when seen in these marvelously sharp and detailed prints, the Lumière Brothers' films belie an artistry and elegance that elevates them above mere scientific recordings. "Train arrival in the station of La Ciotat," for example, which shows a train pulling into a station and the passengers disembarking, contains striking compositions: "the movement is not frontal, is not lateral, there is always a sense of the perspective, the composition of the diagonal."

On many occasions Tavernier compares the compositions of the Lumières to Russian directors of the '20s, as in "Small boat leaving port," and to the work of noted Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu, as in the low-angle composition of two men smoking opium, "Indo-china: Opium den." Other compositions provide multiple levels of action, as in "Carnaux: Taking out of the coke oven": factory workers in the foreground remove red-hot coke from an oven while workers on an upper level haul materials in carts. In another film, "Washerwomen on the river," we see a battalion of women washing clothes on the lower level, men watching them on the second level, and trucks passing on the top level.

Tavernier is also quick to point out how the Lumières influenced the behavior of the people in front of the camera, such as an "overacting" waiter or some "overworking" railroad workers. In one telling example from "Jumping on a blanket," Tavernier describes how Louis Lumière placed a man at the back of the scene. The man watches as the other men toss their friend into the air. He laughs and throws his arms into the air, keying us into how we should respond to the scene. During another street-scene film, Tavernier speculates that the Lumières paid people to attempt to cross the street and thus add to the action.

Tavernier also supplies some hilarious side notes on the films, as when he comments on a strange film that shows soliders of the French Army vaulting onto a horse: some soliders gracefully land on the horse's back while others unceremoniously bounce off the horse's ass. Tavernier says, "Just seeing the film you can understand why we lost so many wars. I mean this is a thing which was not directed by Yakima Canutt" (the great Hollywood stuntman).

These films serve an invaluable role in documenting life at the turn of the century. Particularly in these beautiful prints supplied by Institute Lumière, the startlingly clear images show horses pulling wagons down city streets, trains passing over bridges, firefighters assembling ladders, and passenger ships sliding into the water. These films provide powerful documentary-style portraits of another era. But the Lumières also created comedy films, such as a delightful film called "Mechanical delicatessen trade," which shows a pig being loaded into one end of a box, and after a large wheel is set in motion, the workers open the other side of the box and pull out sausages, hams, and other pork products.

The Lumière Brothers' First Films is a marvelous document of the Lumière brothers' work. It's filled with amazing street-scenes and powerful compositions. Their work is much too often underestimated in America, where the work of Edison is sometimes emphasized over the Lumières. But these are the films that made the world excited about cinema. As Louis Lumière said, "The motion picture entertains the whole world. What could we do better and that would make us more proud?"

In the past, the films of Auguste and Louis Lumière have principally been available in badly-worn dupes, making it difficult to appreciate their work. Now, Kino on Video (in association with the Institute Lumière) has made available in the U.S. the first-ever authorized collection of Lumière films, mastered from the original 35mm materials. The Lumière Brothers' First Films is an amazing journey that provides us with an enlightening portrait of the birth of cinema.

In the past, the films of Auguste and Louis Lumière have principally been available in badly-worn dupes, making it difficult to appreciate their work. Now, Kino on Video (in association with the Institute Lumière) has made available in the U.S. the first-ever authorized collection of Lumière films, mastered from the original 35mm materials. The Lumière Brothers' First Films is an amazing journey that provides us with an enlightening portrait of the birth of cinema.