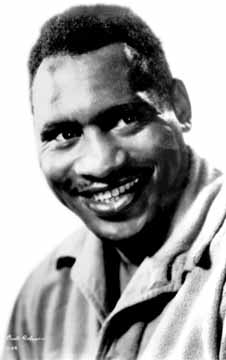

Paul Robeson and John Laurie in Jericho.

(©1998 KINO ON VIDEO. All rights reserved.)

Around 1930, Robeson and his wife Essie moved to London where much of Robeson's political and spiritual consciousness would be solidified. In the decade to follow, Robeson would embrace the bond he felt to his ancestral Africa and reject the aping of white cultural values. These beliefs would seep into many of Robeson's films, including Jericho and Song of Freedom. In the '30s, Robeson also took his first trip to the Soviet Union--a trip that marked the beginnings of his involvement with the Communist Party in America, a fact that would later come to dominate his image and nearly ruin him in the Red Scare of the late 1940s and 1950s.

Robeson was truly the first great black film star who had any control over his screen image. In fact, he was the first black person in the film industry to demand and receive the right to "final cut" and approval of his films. Robeson was extremely careful of the roles he chose because he wanted to create screen images that would give strength and uplift the members of his race. Much of what has been written about Robeson's films in recent film history has tended to disregard the conscientiousness Robeson took to his film roles. Instead, writers have focused on the colonialism of his British films or the subservient roles his American film characters tended to take under the white protagonists. These approaches are easy to take from a position of late-twentieth century cultural awareness, but they deny the vast differences between the black representations in Robeson's films and the majority of other films of this period.

The stifling limitations of black character possibilities in America led Robeson to make most of his later films in England where colonial attitudes of incorporation reigned over outright discrimination and segregation. Robeson's English films all show integration as a matter of fact and find white and black characters existing in almost Pollyanna-ish togetherness. This is no doubt due to England's preference for class over race as a limiting factor. However, even class stratification would be called into question in a film like Big Fella.

The importance of Robeson's films cannot be understated. Robeson was a successful star both on the stage and screen as well as having a successful concert singing career. One need only look to other black screen images of this time to understand the contribution Robeson made to the progress of the representation of blackness. While the movie screens of the 1930s largely only saw the motherly mammy figure (emblematically found in Gone With the Wind) and the lazy, coon stereotype (played to its pitiful height by Stepin Fetchit), Robeson gave the film audience many strong, masculine, sexed, proud and culturally aware figures to emulate. While these portrayals reflect the time period they were made, they also display a remarkable level of modern black consciousness unseen again on movie screens for nearly 30 years.

On the 100th anniversary of his birth, KINO ON VIDEO has made available four of Robeson's finest films in wonderfully restored versions for all of the video market to enjoy. All the films have been digitally remastered from original source material, with Big Fella getting treatment from a 35mm nitrate print restored by the Library of Congress. These films provide testament to the power of Robeson's screen image and his unforgettable voice (arguably the greatest baritone of his generation).

For detailed reviews on each movie in the series, select the titles below:

Body and Soul

Song of Freedom

Big Fella

Jericho

"The Paul Robeson Centennial Collection" is a new four-cassette video series from KINO ON VIDEO. These videos include Body and Soul (1925), Song of Freedom (1936), Big Fella (1937), and Jericho (1937). Suggested retail price: $24.95 each. For more information, we suggest you check out the Kino Web site: http://www.kino.com.

Chris Norton is an editor of Images who received his B.A. in English and Film Studies from Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan and an M.A. from New York University in the Department of Cinema Studies. He currently resides in Manhattan. Chris welcomes comments or questions about his review. You can reach him at norteiga@aol.com.

|

On the 100th anniversary of his birth, KINO ON VIDEO has released four previously unavailable Paul Robeson films on videotape. Restored from original source material, "Paul Robeson: The Centennial Collection" contains the musicals Song of Freedom (1936), Big Fella (1937) and Jericho (1937), as well as Oscar Micheaux's bold and notorious 1924 silent Body and Soul.

On the 100th anniversary of his birth, KINO ON VIDEO has released four previously unavailable Paul Robeson films on videotape. Restored from original source material, "Paul Robeson: The Centennial Collection" contains the musicals Song of Freedom (1936), Big Fella (1937) and Jericho (1937), as well as Oscar Micheaux's bold and notorious 1924 silent Body and Soul.