During the early comedies of most screen comedians, you can see them working on their characters, trying certain characteristics as they honed their on-screen personas. Harold Lloyd would imitate Charlie Chaplin in his Lonesome Luke comedies before perfecting his bespectacled, everyman character. And Chaplin would play a variety of rambunctious characters in his early films at Keystone. However, from his first comedies, Buster Keaton's trademark stone face was evident.

During three years of apprentice work with Fatty Arbuckle, Keaton would occasionally smile, and even laugh, but even then, Keaton fought against reactions. His character's most recognizable trait--an unwavering dead pan expression--had already taken firm root, and by the time he began making his own shorts in 1920, Keaton's screen persona was set. In a very real sense, however, Keaton had been working on his screen persona since he was only four years old. It was at this young age that Keaton had entered the family vaudeville act. Wielding a mop, his father would smack young Buster in the face, and Buster would stare dumbfounded for several seconds before muttering "ow." The stone face was born.

When he was 25 years old, Keaton received an offer from producer Joseph Schenck to make his own solo comedies. After watching Arbuckle make movies during their three years together, Keaton was ready to go it alone. He'd paid close attention to Arbuckle and the mechanics of filmmaking.

The subsequent movies that Keaton made for Schenck are among the greatest screen comedies ever created. And now this entire group of comedies is available on DVD from Kino On Video. When originally released on laserdisc in 1995, "The Art of Buster Keaton" was a revelation. Thanks to the vigilant restoration work of David Shepard, Keaton's classic screen comedies were available in new digitally mastered transfers culled from the best surviving sources. Now these comedies are available on ten separate DVDs.

Keaton's association with Joseph Schenck lasted until 1928. During this remarkably fertile period in Keaton's career, he made 19 short comedies and 11 feature films--including such American classics as The General (1926), The Navigator (1924), and Sherlock, Jr. (1924). However, in 1928, Keaton made (in retrospect) the worst decision of his career. He signed with M-G-M, a studio with no understanding for the individualistic filmmaking method employed by Keaton. He never began movies with finished screenplays. He had beginnings and endings, but he expected the middle to work itself out during the filmmaking process. M-G-M insisted upon complete, studio-approved screenplays before the cameras started rolling.

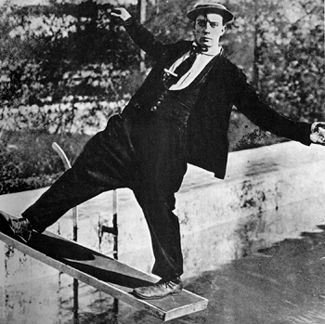

Keaton's first film for M-G-M, The Cameraman (1928), was filmed according to M-G-M's guidelines. When it was also the most financially successful film of Keaton's career, M-G-M considered their practices vindicated. Instead of giving Keaton more freedom in return for his success, M-G-M clamped down further--and Keaton became miserable. Adding to his troubles, Keaton's marriage to Natalie Talmadge was deteriorating. Contributing in no small part was Keaton's habit of frequently drinking and partying at his trailer on the M-G-M lot. He continued working at M-G-M, eventually being teamed with Jimmy Durante--a relationship that forced Keaton into a subordinate role as Durante's constant jabbering stole the attention. Keaton's career never recovered from M-G-M's indifference. By the end of the '30s, Keaton was simply a gag writer, providing ideas to other comedians, such as the Marx Brothers and (in the '40s) Red Skelton. Until he was rediscovered by critics and audiences alike in the '60s, Keaton survived on bit roles (e.g., he was part of the "waxworks" in Sunset Boulevard and he played a beach bum guru opposite Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello in Beach Blanket Bingo). But from 1920 to 1928, Buster Keaton created a remarkable body of work. Keaton loved gadgets, as can be seen in The Scarecrow (1920), where his one-room home is rigged with ropes and pulleys that allow him and his roommate to change the room's look and purpose in just a few moments. The record player, for example, doubles as the stove and a divan doubles as a bathtub. In his first short to be theatrically released, One Week (1920), a build-it-yourself house kit takes center stage as Keaton and his bride attempt to follow the building instructions and build their love nest. But Keaton's rival misnumbers the crates and the Keaton's end up with a bizarrely distorted home. And in Our Hospitality (1923), Keaton utilized an unusual narrow-scale train with cars that resembled stagecoach carriages. But mention the name Buster Keaton today and people tend to think of the stunts--such as the truly remarkable sequence from Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928) where a hurricane rips the front off a house. It falls on Buster, but he neatly slips through an opened window, oblivious of his danger. One of Keaton's earliest comedies, Neighbors (1921), shows him utilizing several stunts: to reach his girlfriend in the apartment building next door, he literally climbs up the sheer face of the building, and later he takes part in an amazing acrobatic stunt where he moves between apartment buildings by riding on the shoulders of other men--stacked three high!--as in a circus act.

stills from the films of Stunts like these didn't necessarily leave Keaton unscathed. His body was marked with scars from stunts that had gone awry. In Sherlock Jr. (1924) a blast of water from a water tower spout sent Keaton crashing to the railroad tracks below. Years later, a doctor asked him, "When did you break your neck?" X-rays indicated Keaton's neck has been broken and subsequently healed. Keaton thought back and remembered hitting the back of his head on the railroad rails when the water pressure from the tower took him by surprise and flattened him against the ground.

But the most distinctive trait of Keaton's filmmaking technique comes during the less chaotic moments of his movies. For example, in The Goat (1921), Keaton tries to evade a pursuing policeman by holding onto the spare tire on the back of a car. As the car begins to move down the street, Keaton expects to move with it, but the tire is actually part of a sign advertising "vulcanizing." As the car disappears down the street, a bemused Keaton climbs off the sign. Keaton was an expert at comic misdirection. In One Week, for example, Keaton and his bride attempt to move their home, but the house becomes stuck on railroad tracks. An approaching train sends them scurrying to push the house off the tracks, but it won't budge. They give up, run a few steps away, and wait for the impact … but the train slips past--on a parallel set of tracks. They relax. Everything's okay … and then a second train, from the opposite direction, plows into the house and demolishes it.

These characteristics (and many others) made Keaton a truly unique performer. Stunts weren't featured in all his films. Go West (1925), for example, is relatively low key--the story of a man and his cow. And not all his movies featured gadgets. While The Electric House (1922) is filled wall-to-wall with gadgets, such as a toy train set that carries food to the dinner table, My Wife's Relations (1922) forgoes gadgets while focusing on the motley group of relatives that Buster acquires after an accidental marriage ceremony weds him to a woman who wanted him arrested for breaking a window. (The judge/justice-of-the-peace only speaks Polish and misunderstands why they've come to his court.)

When Keaton was placed at the service of a fully-developed plot, the characteristics that made him an individualistic talent were suppressed. Comedies such as Spite Marriage (1929) and Free and Easy (1930) are pleasant but they're also largely anonymous. The same could be said of Keaton's first feature film, The Saphead (1920). Before Keaton embarked on his classic silent comedies, producer Schenck loaned him to M-G-M. The movie, based upon a Broadway success that starred Douglas Fairbanks, is agreeable, but little of the comedy required Keaton's unique talents. Strangely enough, The Saphead foretold what would happen to Keaton once he joined M-G-M fulltime.

Allowed to make movies his own way, Keaton gave the world some of the greatest comedies ever made, but forced into the Hollywood system, he languished. However, for nine years, from 1920 to 1928, Buster Keaton was given the freedom to weave his cinematic magic, and the proof is on "The Art of Buster Keaton" DVDs from Kino. This is essential cinema.

Buster Keaton's entire output from his association with Joseph Schenck is now available on DVD from Kino On Video (distribution by Image Entertainment). These shorts and feature films are available on ten DVDs. Suggested list price: $29.99 each. For more information, check out the Kino and Image Entertainment Web sites.

The DVDs contain the following features and shorts:

|