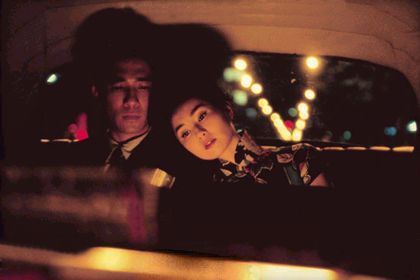

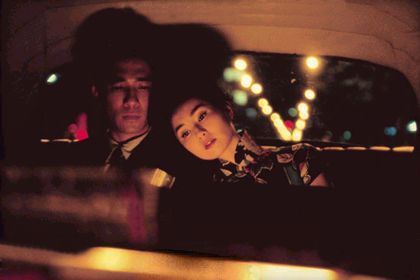

| stills from In the Mood for Love |

|

| [click photos for larger versions] |

The protagonists, we can clearly see, are in tune with their sensual sides. She wears a devastating series of restrictive, floral print dresses that show no skin but which outline her form with sharp precision; he smokes a cigarette like the prototypical French New Wave anti-hero, all attitude and posturing. When their spouses run off together to Japan, we expect their formal attitudes to thaw, but instead they find solace in each otherís unapproachability. A revelatory scene at a diner becomes a conversation about handbags and ties: itís a skittish dance around the unspeakable that acknowledges everything but verbalizes close to nothing. Repelled by their spousesí indiscretion, they find themselves in a world where illicit sex mocks them at every corner. Mrs. Chanís boss carries on an extra-marital affair between power meetings; in one scene, he asks her to choose a suitable birthday present for his mistress. Mr. Chowís co-workers, as overweight and ungainly as he is lean and stylish, ask to borrow money so that they may visit a brothel. Our protagonists comply without protest, helping others commit that which they would never do.

Content to remain polite acquaintances, or maybe scared of turning into their errant spouses, Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan (they never address each other informally) become prisoners of their own good behavior. Their bottled-up sexuality plays tricks on their minds, inverting the chronology of crucial events. Her secret visit to his room takes place after he discovers her lip-sticked cigarette on his ashtray. And confrontations seem to occur before they actually happen: what we think is Mrs. Chan accusing her husband of infidelity turns out to be a dress rehearsal, with Mr. Chow as the stand-in. Imagination supersedes reality. Wongís camera is in search of what it canít see, that sweaty anticipation or elusive frisson that courses through us when romance, or the memory of it, is near. Approximating loveís incoherence, Wongís sense of time progresses fitfully, impatiently and impulsively. A day occupies the same space as a week. As their relationship attenuates towards the inevitable, time takes even bigger strides. The final sequences, set in such places as Singapore and French Cambodia, are separated by months, then a year, and then three years. Love recedes exponentially; it never fully disappears, but, as Mr. Chow states in the end, grows increasingly "blurred and indistinct" with time. Panning across ancient ruins that might symbolize love long since abandoned, the final scene feels unnecessary. Every second of the movie has been an act of remembrance, a sifting through of artifacts from a dead era.

Beautiful without being fatuous, In the Mood for Love displays occasional flashes of cynicism. "What would I be if I wasnít married," he asks, and her reply is "Maybe happier." Their jaded temperament, while never angry, cools the movieís overripe sensuality, shading it with self-doubt and indecision, and adds new dimensions to the movieís ravishing surface beauty. The cinematography by Christopher Doyle and Mark Li Ping-Bin becomes almost tragic as the would-be lovers fumble in the shadowy Hong Kong alleyways. Their bodies partially concealed, they never reveal themselves fully to each other. The set design and costumes evoke sixties sexual arrogance and often have double meaning, from the red curtains that guide them to a sexual encounter that never happens, to Mrs. Chan's dresses which are dyed with intense, exotic patterns but whose high collars and low hemlines fit her like chastity gear. At once exuberant and pessimistic about love, Wong Kar-Wai never plays us the titular song, as he did in his previous film Happy Together. But this denial, like the other forms of denial in this gorgeous and intelligent movie, only heightens that which isnít physically experienced. With patience and empathy, Wong Kar-Wai distills love, sexual, romantic or otherwise, to its barest, most basic ingredients.