DVD REVIEW

Year: 1997. Directed by Werner Herzog. Starring Dieter Dengler and narrated by Werner Herzog. DVD release: Anchor Bay Entertainment Review by David Ng In recent years, the documentary has become a more intimate medium, one in which the director not only plays a visible role but also transforms himself into his own subject. The result can be a kind of visual essay that presents facts in a subjective way. The most recent example is Agnes Vardaís documentary The Gleaners and I (2001). As the title indicates, it is a highly personal film. The elfin Varda uses digital video to record the scavenging habits of French society throughout the ages. Shuttling between past and present, city and countryside, Varda narrates the film and serves as cameraman, but she is also one of its many subjects. In her cottage, completely alone, she trains the camera onto her own hands and comments on their spots and wrinkles. Later, she digitally inserts herself into the famous Millet painting The Gleaners, which portrays nineteenth century peasants scavenging a harvested wheat field. Positioning herself carefully between two of the peasants, Varda becomes of the object of her own scrutiny.

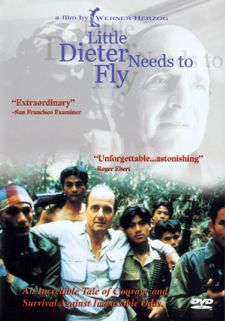

This notion is present, though in much subtler form, in Werner Herzogís 1997 documentary Little Dieter Needs to Fly, which is now available on DVD from Anchor Bay Entertainment. Unlike Varda, Herzog doesnít appear on-screen, but he makes his presence known in other ways, in the form of narration, and more significantly, through his idiosyncratic telling of the life of Dieter Dengler, a German-born Vietnam War veteran. The film opens with a quotation from the Book of Revelations: "And in those days shall men seek death, and shall not find it, and shall desire to die, and death shall flee from them." We are introduced to a middle-aged Dengler who walks into a tattoo parlor and stops to ponder a design of Death in a fiery, horse-drawn chariot. "Death didnít want me," he says, referring to his successful escape from Laos.

The story of Dieter Dengler is a harrowing one. Born in a small village in Germany, he suffered intense poverty during the second World War. At the age of 18, he emigrated to the United States to realize his childhood dream of becoming a fighter pilot. He enlisted in the Air Force and later the Navy, and was shipped off to Vietnam in 1966. On his first mission his plane was shot down over Laos. Dengler was captured by the North Vietnamese and endured a prolonged captivity. While a prisoner, Dengler and several other American POWs planned a daring escape, the details of which are recounted by Dengler in breathless, painstaking commentary. Dengler also re-enacts certain parts of his adventure, traveling back to the very jungles he had fled thirty years before and subjecting himself to many of the same forms of torture and brutality.

What differentiates Little Dieter Needs to Fly from the conventional documentary is Herzogís eerie identification with Dengler. Beyond topical similarities (both are Germans who, at the time of filming, reside in Northern California), they share an equally intense relationship with death. At one point during his escape, Dengler has a vision of his dead father guiding him along a river bank. Much later, Dengler encounters a bear which follows him around waiting for him to die. "The bear meant death to me," Dengler says, "and in the end it was my only friend." Transmuting Dengler into an existential character of the sort found in his fictional films, Herzog subverts the tradition that documentary subjects be kept at a certain distance. Without any warning, he blurs the distinction between Dengler and himself by using double narration, making it difficult, sometimes impossible, to determine the identity of the speaker. It is an act similar to Vardaís insertion of herself into the Millet painting: it merges the filmmaker with his or her subject, violating every notion of objectivity, and transforming the film into a specimen of self-reflection.

This then begs the question, "How much of the movie is staged and how much of it is real?" There are parts of Little Dieter Needs to Fly that are unequivocally the creation of its director, such as the reenactment of his captivity in which the middle-aged Dengler is handcuffed and then pushed and prodded by an ominous bunch of soldier-actors. But there are also unscripted moments that exist alongside the artificial ones, moments like Denglerís gentle reassurance to a local villager after demonstrating to him a particularly vicious amputation. "Donít worry," he tells him, "itís just a movie." And further still, there are moments that could be both, scripted or unscripted, such as in the final scene where Dengler finds himself in an enormous airfield with fighter jets extending as far as the eye can see. To be surrounded by so many planes, Dengler tells us, is like being in heaven.

Divided into five distinct chapters, with titles like "The Man" and "The Dream," the movie is selective in choosing which aspects of Denglerís life to explore. The majority of his post-war life is omitted, as is his personal and professional life. What remains is a curiously shaped experiment of projected obsessions and vicarious confessionals. In this respect, the DVD version of the movie has a distinct albeit regrettable advantage over the theatrical version. Dieter Dengler passed away in 2001, a victim of Lou Gehrigís disease. The DVD includes footage from the full military funeral which took place at Arlington National Cemetery. Acting as a sort of coda, it seems to say that death eventually did come for Dieter Dengler, not in the form of a gun to the head or a knife to the throat, but as a gentle tap on the shoulder.

Little Dieter Needs to Fly is available on DVD from Anchor Bay Entertainment. Special features: widescreen presentation (1.85:1) enhanced for 16x9 televisions; production notes; and Werner Herzog bio. Suggested retail price: $29.98.

|