6 A significant portion of this fan discourse centered on home and family--with the star photographed, surrounded by family members, in his/her tastefully lavish home (more than occasionally a "dream house")--a centering that at once related the star to the similar elements (home, family) in the fan's life, even as it elevated the star, via his/her beauty, fame, wealth and possessions, far above the fan. In this respect, the magazine discourse played on the same presence/absence that many have identified at the heart of cinema itself: e.g.,

"The cinema fascinates because we alternately take it as real and unreal, that is, as participating in the familiar world of our ordinary experience yet then slipping into its own quite different screen world. Only an unusually strong act of attention enables us to focus on the light, shadow, and color without perceiving these as the objects they image" (Andrew, 42).

Another vital, and often overlooked, function of the fan magazine (and other forms of printed-graphic publicity materials) was to take images of the stars out of the theaters per se and circulate them physically through wider realms of the general culture. Movie-going--then, now and for the foreseeable future--is a highly specialized activity, taking place in what sociologist Erving Goffman would designate a separable place: "A social establishment is any place surrounded by fixed barriers to perception in which a particular kind of activity regularly takes place" (228). The effect of fan magazines, and various other types of publicity, was, in essence, to forge a link between the specialized arena (the movie theater) and all the arenas of everyday activity (the home, the office, modes of public transportation). Here, fans could read about and possess images, both mental and visual, of their "favorite" stars--"favorite" being a necessary category to commodification--in a way closely related to, but distinct from, the way they related to the stars' images on the screen. Anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker, in her classic study, Hollywood: The Dream Factory, notes how the discourse on stardom domesticates the stars much in the way in primitive societies totemic heroes were brought into the home through effigies and other representations:

The relationship of fans to their stars is not limited to seeing them in movies, any more than primitive people's relationship to their totemic heroes is limited to hearing a myth told occasionally. . . . In our society the identification of fans with their movie heroes may be equally intimate, but for different reasons. Fan magazines give details of the star's domestic and so-called private life, with pictures of his home, his garden, his swimming pool, his family, his dogs and his cats. The columnists in the daily paper expand this with what type of underwear he wears, whether he prefers noodle soup or tomato. The fan is permitted to have a peep show into night clubs and into bedrooms, and knows with whom the hero dines and dances, to what parties he goes and to whom he is engaged, a ritual term for "affair." (249).

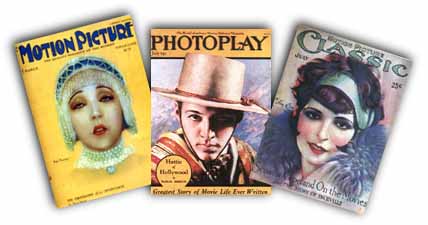

By the 1920s there were more than a dozen major fan magazines, with Photoplay's circulation running over two million. The movie stars had become household gods.

Nonetheless, fan magazines did not always or completely function as publicity arms of the studios, as mere producers of totemic images that could be directly converted into further box office receipts. For instance, while other producers followed Laemmle's early lead by attempting to create a highly visible corporate identity for their stars, popular culture notions of individualism tended to reduce the production company to an "accidental" quality, the "primary" quality being "star quality" itself: in the public eye, Mary Pickford was a famous player both before and after she was a "Famous Player."

Publicity photo of Mary Pickford.

In addition, as Gaylyn Studlar has recently and persuasively argued,

The unprecedented rise of the fan magazine's popularity in the 1920s took place within a broader ideological framework marked by women's growing economic and sexual emancipation and the widespread belief that changes in women's behavior were contributing to a radical subversion of American gender ideals. [Yet, these magazines] "in comparison with general cultural discourse aimed at men. . . often evidenced a progressive view of women's changing sexual and economic roles" (9-10).

For instance, in portraying that emblematic young woman of the 1920s, the flapper, "the films appear more conservative than the fan magazines" (20). Still and all, fan magazines were commercial ventures that depended on the film industry for their existence, and so for the most part these publications "adopted strategies to channel women into ethnically, racially, and nationally normative modes of heterosexual sexual romance in a nativist culture" (26)--in other words, to maintain them as fit individual members (and willing consumers) in the American movie-going community.

In time, with some of the more rebellious stars of the 1930s and 1940s (like Bette Davis, see below), the fan discourse of magazines and newspapers sometimes became a forum for the stars' discontent, with the feisty independence of these stars turned into a positive part of their total image. In addition, the rise of gossip columnists like Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper, the most powerful people in Hollywood not created by the studios, meant millions of people a day read about the stars in contexts that could only be partially controlled by industry forces, a fact bound to make the bosses nervous in a town still mindful of the effects of the early 1920s scandals (Arbuckle, Wallace Reid, William Desmond Taylor).

The fan magazines and like vehicles of the classical period by and large called for, and obviously received, the "willing suspension of disbelief" on the part of readers.7 More often than not, the star's latest picture, latest co-stars, latest marriage, latest home are the most satisfactory, with past failures redeemed and past triumphs echoed. As Michael Wood has judged about American movies, "Movies assuage the discomforts of blurred minds; but they also maintain the blur. That is their business" (21). So too was it the business, whatever their small deviations, of the fan magazines.

page 3 of 9

Go to:

Introduction

Part One: The emergence of the star system

Part Two: The real, the "reel," and fan magazines

Part Three: The selling of stars

Part Four: The close-up and Alice Adams

Part Five: Cultural self-importance and A Star is Born

Part Six: Studio battlers--James Cagney and Bette Davis

Part Seven: The power of stars, the power of agents, and Jimmy Stewart

Wrap-up

Notes

Works Cited

Brian Gallagher is a professor of English and film at the City University of New York (LaGuardia).