|

The car breaks down on a trip

to the race track in Killer of Sheep.

Killer of Sheep holds many of the trademarks of realist and neo-realist film. Whereas the films of Jean Renoir and French poetic realism were so influential on the Italian neo-realist period, the neo-realist period obviously influenced Burnett deeply. Killer of Sheep deals with a common man, Stan, and his struggle to support his family and provide male leadership. The realist concern with the lower and marginal classes of society and the contemporaneity of realist texts are present in Burnett's film. This was the world at hand, the world both Burnett, and neo-realist directors like Rossellini and Visconti knew all too well. Contemporaneity is an element that is vital to the realist text. Paisan, in particular, dealt with issues that were pertinent to Italian life during the occupation of allied forces right before, and during, the time the film was made. Killer of Sheep also dealt with issues pertinent to the life of South-Central at the time it was made. Contemporaneity is an important aspect in realist films only because of the social consciousness that these pieces strive to alert and awaken. A need to see reality dealt with as it truly exists. Andre Bazin said of the post-war Italian cinema that it "was noted for its concern with actual day-to-day events...This perfect and natural adherence to actuality is explained and justified from within by a spiritual attachment to the period"(20). Burnett's piece exists as an extension of his own spiritual attachment to his period. Burnett grew up in South-Central and put on film that which he knew from his own life. Killer of Sheep deals exclusively with the day-to-day events of Stan's family. With humor, wit, and an eye for minutia, Burnett explores the issues of hope, longing, and futility, in short, the range of human emotions, through such events as a failed trip to the race track, the loss of a used car motor to make the American status symbol run again, and the drudgery of work in a slaughterhouse. This contemporaneity and actuality are not only a tie to Italian neo-realism, but also a link in allowing the film viewer into the reality of life for the inner city black family.

Men at work butchering in Killer of Sheep.

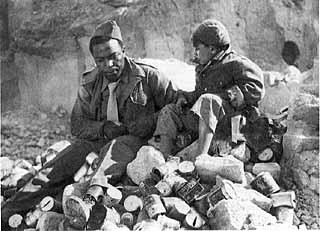

Stylistically and visually, Killer of Sheep shares much in common with Italian neo-realist productions. Both Italian neo-realist film and Burnett's piece use grainy black and white stock, a fact that has more to do with the means of production available than artistic choice. Expensive film stock and studio settings were not an option due to the lack of funds and the dominance of mainstream film over advanced means of production. However, the film stock used serves to add to the effect of realism with its obvious parallel to documentary film stock. The use of natural settings is also a hallmark of both. When comparing Paisan with Killer of Sheep, one is amazed at the similar mise-en-scene. Despite the fact of being separated by over thirty years, and the completely different locations, both film’s settings are strikingly similar. Both films portray a bombed out milieu, where rubble and abandoned buildings dominate the landscape; Italy's landscape scared by the years of war, South-Central's landscape scarred by years of urban decay, uprisings, middle-class flight, and businesses fleeing the inner-city.

An American solider and a boy

in Roberto Rossellini's Paisan.

Phyllis Rauch Klotman has commented on the neighborhood in Killer of Sheep saying, "its dirt and desiccation, becomes...a defining and limiting presence in the film"(97). In scenes that are almost identical, Paisan's children play on a heap of rubble as do the children of Killer of Sheep. This similarity resounds with more than a simple visual parallel. It is an indicative of the war that plagues the inner-city and its inhabitants. Whereas the allied forces tried to bring normalcy back to Italy, the inner city is left to rot by the rest of America, its inhabitants pushed far from the consciousness of suburban life. Burnett, much like Rossellini, brings to the forefront this plague of neglect.

Boys at play in the dirt

in Killer of Sheep.

Thematically, Killer of Sheep delves mostly into the arena of hope. Hopes can be expressed for every character in the film and every scene centers on a hope of something beyond the current reality. Hope rests in the American symbol of the automobile as Stan and his friend buy, with what little money they have, a used engine to get Stan's car running. This hope is quickly lost as the engine rolls out of the back of their pickup truck and is ruined. Hope rests on a failed trip to the horse track but Gene's car breaks down and the promise of a sure winner is lost. Hope rests in the family life of Stan and his wife but that too is lost as Stan's impotence, due to his nightmarish job in the slaughterhouse, prevents him from sexual activity. Hope rests in the children's play in the ruins of the ghetto which always leads to a child being hurt by thrown rocks, by being assaulted, or by accidents such as when a child skids off a skateboard as he races down a hill. All of these examples of hope end in futility. Hope ending in futility was also a common thematic in neo-realist film. All six of Paisan 's episodes end in futility. In the final episode, the courageous partisan and allied guerrilla fighters are defeated and executed leaving nothing but a feeling of futility for their efforts. In La Terra Trema, the family's attempt at buying their own boat, only ends in failure.

Stan herding sheep in the

final scene from Killer of Sheep.

Despite the many examples of futility in Killer of Sheep, Burnett does not leave us with this feeling. In the end, Stan forcefully herds the sheep into the slaughterhouse showing more emotion than he has for the entire film. Evidently, he has decided to persevere and fight on despite society's place for him. Burnett says of Stan, "Not only does Stan continue to struggle, but he does so without falling into an abyss or becoming a criminal or doing other anti-social things"(Wali 20). Here, we have a departure from other neo-realist texts. Burnett has demonstrated hope and futility, aligning his work with other neo-realist texts, but he has placed the final emphasis on another hope, the hope that the continuing struggle for human dignity and a rightful place in American society is worth persevering. His film refuses to give in to the futility that plagues the inner city. The fact that Killer of Sheep ends with hope and that Stan chooses to continue his struggle are important features of black independent film. As will become evident after the discussion of Nothing But a Man, the "struggle" which produces hope is directly tied to black identity.

page 2 of 4

Page One Introduction

Page Two Killer of Sheep

Page Three Nothing But a Man

Page Four Bless Their Little Hearts

|