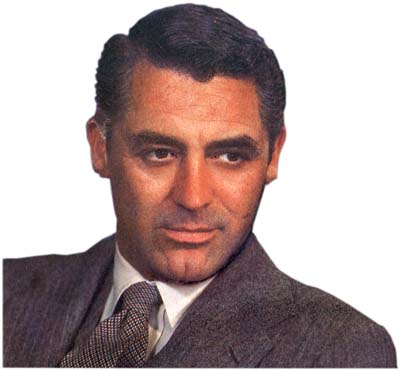

Recently Entertainment Weekly published a special issue--"The 100 Greatest Movie Stars of All Times." Star number 6 was described as follows:

If Hollywood had its own Mount Rushmore, Cary Grant's profile would be the most prominent: the hair that Katharine Hepburn mussed in Bringing Up Baby (1938), the eyes that Eva Marie Saint couldn't quite meet in North by Northwest (1959), the lips that locked so breathtakingly with Ingrid Bergman's in Notorious (1946), and, of course, the cleft chin that fascinated Audrey Hepburn in Charade (1963).

On reading this entry, I was struck at how it contradicted Laura Mulvey's seminal work, "Visual Pleasure in Narrative Cinema," which characterizes the gaze of the camera, and the spectator, as always male and the object of the gaze as always female. Though these looks at Grant described above are all attributed to an on-screen female, it is obvious from the description that the gaze of the shots described forces male and female spectators to look at Grant as an object of desire. Because no other entry in this Entertainment Weekly issue presents such a detailed objectified description of an actor's (or even actress') appearance (the entries on Brando, Redford, Cruise and Gibson acknowledge their looks, but quickly move on to discuss their other qualities), it reinforced my own personal feeling that there might be something special about looking at Mr. Grant.

E. Ann Kaplan (the author of Women and Film: Both Sides of the Camera) contends that traditional male stars, like John Wayne, derived their glamour not from their looks but from the "power they were able to wield within the filmic world in which they functioned" (28). Though Kaplan's association with glamour and power may hold for John Wayne, James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart (or Katharine Hepburn whose appeal EW describes as based on her portrayal of feminine rebellion, "the original liberated woman, on and off the screen, tilting at the windmills of convention and male dominance."), Grant's glamour is directly tied to his objectified beauty, whether it is situationally supported by power or not. EW's entry on Grant goes on to remind us that it was Cary Grant who Mae West first asked, "Why don't you come up and see me sometime?" in She Done Him Wrong (Lowell Sherman, 1933). Grant began his career as the object of an active, female desire.

|