|

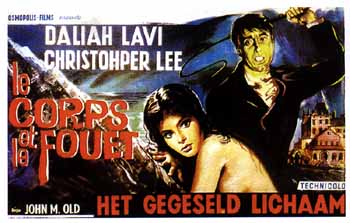

A ghostly child beckons to her

relatives in Kill, Baby, Kill.

Kill, Baby, Kill (Operazione Paura, 1966) contains an even more disorienting doppelgänger. Bava isolated his protagonist, a young gentleman like the one in Black Sunday, in a manor house which is reputedly haunted by the ghost of a young girl (who strikingly anticipates the child-demon created the following year in Fellini’s episode of Spirits of the Dead). The initial confusion caused when the young man encounters the child’s still-living mother, who has surrounded herself with the toys, clothing and other physical remnants of her daughter’s life, is compounded by the appearance of what may be the child herself or her specter or another child altogether. In a climactic scene, the young man pursues an assailant through a series of identical doorways and rooms; but when he finally catches him, he discovers that he has been chasing himself or, at least, an apparition that resembles him. After having played the viewer’s genre awareness repeatedly throughout the film and having characters discuss the nature of the haunting, Bava inserted this event without an explanation. In the fantasy sequence which follows, a dream image reveals a man entangled in a huge web in front of a painting of a cathedral. This shot fades, and the man awakens, now free of the web but standing before the actual building. Is this a dream or not? As with Roger Corman’s ending to the Tomb of Ligeia, Bava exploited the dream context to freely intercut between real and hallucinatory events and compel the viewer to create the distinction between the two. A similar manipulation occurs in What. Not only does Nevenka, a young woman with sado-masochistic proclivities, claim that she is being tormented by a dead lover, but the audience sees several visits to her bedchamber by a dark figure who chastises and caresses her. Of course, the audience is free to assume that these visitations are merely projections of her disturbed mind; but there are certain external, physical manifestations. The lover’s footsteps are heard in one scene; his laugh , in another. In a third, the footprints of his wet boot soles are left behind. As in Black Sunday, the reality of the apparition is reinforced when the spectator is compelled to assume Nevenka’s point of view at key moments through the use of subjective camera. In the final scene, Nevenka is seen kissing her ghostly lover from one, quasi-subjective perspective. A cut to another, more objective angle reveals her embracing the empty air.

Scenes from What. Shot #1 (left) shows the subjective view of Nevenka: she belives Kurt, her dead lover, is with her. Shot #2 (right) shows the view of Nevenka's husband, who is barred from reaching her by an iron gate. Notice the knife in her right hand.

In most of Bava’s work, this manipulation of reality and illusion was character driven. The visceral impact of particular and peculiar techniques, such as the snap zooms and over-rotated pans, stand alone as part of an overall horror/suspense style but may also be keyed dramatically to the emotions of a character. Bava could quickly evoke his genre on a formal level with stylistic resonances to precedent films of his own and others, that is, through standard genre indicators and expectations. What sets Bava’s work apart from most other genre filmmakers is the creation of metaphor and dramatic irony through the interplay of subjective and objective viewpoints and the linking of visual disorientation to character emotion. In the first episode of Black Sabbath (I Tre Volti della Paura, 1963), a nurse steals a ring from the corpse of a woman over whom she has kept a death watch. In the same manner as Poe’s "Tell Tale Heart," her guilt distorts her perceptions, and she is driven mad by her amplified awareness of everyday objects in the house around her. First, she is assaulted by the crashing sound of a drop of water. Then, as she shivers in wordless apprehension, that emotion is objectified by the intermittent glare of a cold blue shop light blinking on and off outside her window.

A blue light surrounds a man returning from

killing a vampire in Black Sabbath.

In the third episode of Black Sabbath, a similar blue light envelops a figure returning from killing a vampire. The light, which grips him like an aura of death, makes it clear to his apprehensive family that he has become one of the undead himself. In Black Sunday‘s colorless world, the simple fear of a character who moves down a corridor without knowing where it leads is underscored by an alternating side light that strikes first one side of the face then the other even as the impulses of fear and curiosity drive the figure hesitatingly forward.

See the hallway scene,

an excerpt from What.

(Animated GIF, 13 frames, 133 KB)

Bava reused this staging in What with the added element of color. As Nevenka walks towards a room where she thinks her dead lover awaits, the sound of a whip and her sensual gasps are overlaid on the soundtrack. As she continues, uncertain what is real and what is illusion, in anticipation of pleasure and pain, the alternating side lights are blue and red, cold and hot.

page 2 of 4

Italian Horror Menu page

Italian Horror: A Brief Introduction

Mario Bava: The Illusion of Reality

Mario Bava's Rabid Dogs

Mario Bava Biography

The Horrible Dr. Hichcock

The Devil's Commandment

Castle of Blood

Nightmare Castle

The Bloody Pit of Horror

Italian Horror in the Seventies

Suspiria

Italian Horror Web Links

Photo credits: Dean Harris, Silent Scream, and Sinister Cinema.

|