|

There are at least two reasons for this failure. Perhaps, much of the blame rests with those prison movies that used the horrors of imprisonment for titillation and shock value. These movies were indifferent to any wider reformist stance. Most at fault were the exploitative films about women in prison made in the 1970s, including New World's "Women's Penitentiary" trilogy: The Big Doll's House (1971), The Big Bird Cage (1972), and Women In Cages (1972). Consequently, those prison films with a genuine reformist stance were frequently viewed as simply more refined versions of their crass counterparts. The second reason for the prison film's failure to encourage reform is more political -- that the only reason any prison film contributes to the penal debate is because passages already exist for change to occur. In the case of I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang (1932), Nellis & Hale (1981) point out the publicity at the time concentrated on how the use of chain gangs was un-American and barbarous, hence the billboard poster advertising the film:

"Watch the crowds as they come out! Women . . . with tears in their eyes! Men . . . ready to fight!" (Quoted in Querry 1975, p.28)

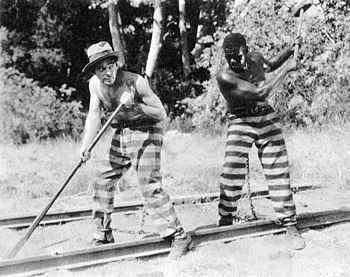

Chain gang convicts plotting an escape

in I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang.

Despite the apparent failure of the prison film to change the penal system, its popularity is unquestionable. Root (1982) argues that the attraction of the prison film is intangible:

"It isn't immediately obvious why prison films should occupy such a prominent place with the film going public. Most prison films . . . don't have glamorous locations, rarely involve international stars and usually have very little sex in them." (Root 1982, p.14)

Yet, the prison genre has survived -- even thrived -- throughout its history. Perhaps most appealing to audiences, prison films give us an opportunity to share in the criminal world, to move in circles of illegality from the safety of our theater seats, to see the "extreme sadism" (Root 1982, p.14) of prison life, and to identify with those prisoners who revolt against inhumane treatement. This viewer experience is positively encouraged by prison films: the audience is locked up with the inmates, they listen as escape plans are devised, and they watch as the inmates exercise in the yard. It is perhaps from this vicarious, voyeuristic impulse that the prison film derives its power.

page 6 of 6

References

References

Page 1: Introduction

Page 2: The Prison Movie as Genre

Page 3: The Prison Machine

Page 4: On Entering Prison

Page 5: Other Themes

Page 6: Captured On Film

Paul Mason graduated with an LLB (Hons) from University of Southampton in

1991. He went on to complete a doctoral thesis at the University of the

West of England, Bristol entitled "The Depiction of the British Prison on

Televison 1980-1991." He is Co-Ordinator of the Southampton Institute

Centre For Media & Justice. He is currently organizing a national conference --

"Cameras In The Courtroom" for February 1999.

|