|

Rod Cameron at a disadvantage

in Secret Service in Darkest Africa.

Part of the problem may also have been the nature of chapter endings. As serial makers strove to place heroes and heroines in mortal danger at the end of each episode, the serials emphasized the work of stunt men and de-emphasized stories and characters. The work of great stunt men such as Yakima Canutt, David Sharpe, and others shouldn't be underestimated; however, with the emphasis on death-defying stunts, serials became increasingly mechanical, predictable, and uninventive. Maybe if the serial had evolved along different lines--giving us chapter endings that pointed toward new story developments, instead of emphasizing the stunts--the serial could have survived. But instead, the serial was treated as simply an assembly line product with pieces that could be mixed and matched.

Also contributing to the problem, an anti-trust court ruling in the late '40s forced the studios to divest themselves of their theaters. Studios then considered the serials to be a luxury (along with shorts and B movies). All the attention went to feature films. As moviemaking costs soared, serial budgets were slashed, necessitating extensive use of stock footage. Heroes and heroines wore costumes that matched those used in earlier serials, allowing the same action scenes and cliffhangers to be recycled. For example, action scenes from Jungle Girl and The Phantom were reused over ten years later in Panther Girl of the Congo and The Adventures of Captain Africa, respectively. Heroes also suffered as casting choices were made to match stuntmen on the studio payroll, leading to a legion of hopelessly dull heroes.

With the growth of television, the serial was living on borrowed time. TV shows such as Sky King, Hopalong Cassidy, The Gene Autry Show, and The Lone Ranger soon appeared. Serial star Ralph Byrd even reprised his portrayal of Dick Tracy for television. Why go to a theater when you can see similar stuff for free at home? Complicating matters further, psychologists and parents began to worry (some would say they became hysterical) about the violence in serials and comics. They pressured studios and publishers to reduce the mayhem.

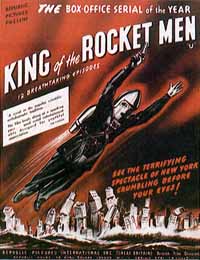

Movie poster

for King of the Rocketmen.

Universal saw the end was near and canceled serial production in 1947. Republic and Columbia struggled into the '50s, producing fewer and fewer serials each year. For awhile it looked like a rejuvenation of interest in science-fiction might save the serial. King of the Rocketmen (1949) gave us a jet-suited do gooder who soared the air to restore justice. His suit displayed three knobs. One said "on" and "off." Another said "up" and "down." And the last said "fast" and "slow." Republic reused the flying footage twice, in Radar Men from the Moon (1952) and Zombies of the Stratosphere (1952). However, notwithstanding the flying sequences, these serials are a remarkably mundane and ordinary lot, with dull, interchangeable heroes. Comic book artist Dave Stevens rekindled some interest in the rocketmen serials with his reprisal of the rocketmen storyline in The Rocketeer, a popular comic book of the '80s, but his enticing Bettie Page look-alike sketches of the story's heroine were responsible for much of the hubbub. For the same reason, the rocketmen serials continue to appear on television, while some of the best Witney/English serials haven't played television in decades.

With an audience that grew increasing disinterested in serial exploits, Republic finally curtailed serial production in 1955 with King of the Carnival, which reused extensive footage from Daredevils of the Red Circle. Columbia would limp along with three final Spencer Gordon Bennett serials before giving up in 1956 with Blazing the Overland Trail.

While the serial is now long gone, part of its heritage lives on in the television series. Instead of forcing us to spend an entire week waiting to find out how the hero will escape the villain's latest terror, we now must wait only until the commercial break is over. Some shows, such as The Time Tunnel and Lost in Space, actually used cliffhanger endings—but only as small overlaps into the next week's episode. Soap operas come the closest to using real cliffhangers. For example, the evening soap opera Dallas left millions of viewers to argue throughout the summer about who shot J.R.

Thanks to video we can now see the cliffhangers again, but we can never really experience them—to spend a week of agony waiting to find out how the hero escaped the peril, to run past movie posters and lobby cards, to settle down in the fifth row, popcorn clutched in one hand and a soda in the other (with candy bars stuffed in coat pockets), and to then see the screen burst to life—those days are long gone.

However, the legacy of the serial lives on in feature films, such as Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark. Raiders even manages to begin with a sequence that remarkably resembles a slide over from a previous cliffhanger: Indiana Jones flees through a cave tunnel as a giant boulder rolls after him. Later, his fight aboard a truck recalls the work of the great stuntman Yakima Canutt. (Compare this scene with the stagecoach scene in chapter eight of Zorro's Fighting Legion). And Darth Vader of Star Wars is a direct throwback to the masked villains of the serial's golden era. (Compare him with the Lightning in Fighting Devil Dogs.)

The serial is now dead. Its history is in some ways a disappointing one, for the serial failed to progress past its own narrow limitations. Even the best serials—such as Flash Gordon, Spy Smasher, Zorro's Fighting Legion, Dick Tracy, Daredevils of the Red Circle, The Lone Ranger, Mysterious Dr. Satan, The Adventures of Captain Marvel, and The Perils of Nyoka—are frequently beset by wooden performances, confusing plots, and all too familiar cliffhangers. But when the serials worked, the results provided a rare brand of movie magic, the kind of wizardry that inspired many young moviegoers, including George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, to become movie directors. The serial will continue to live in their movies, finding a whole new generation of fans for decades to come.

page 5 of 5

The Serials: An Introduction

Page 1: In the Theaters

Page 2: The Beginnings

Page 3: Enter Flash Gordon

Page 4: The Golden Age

Page 5: The Downfall

The Phantom Empire

Flash Gordon

Dick Tracy

The Fighting Devil Dogs

Zorro's Fighting Legion

The Shadow

Mysterious Dr. Satan

Spy Smasher

Perils of Nyoka

The Tiger Woman

Serials Web Links

|