| ||||||||||

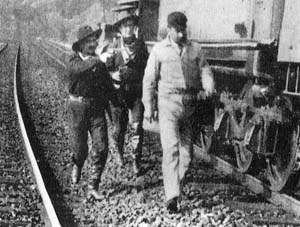

The hold-up scene from The Great Train Robbery. Prospecting: Thomas Edison, the inventor of motion pictures, was also the first to use the new technology to channel the Western myth. Several of his earliest films, dated 1894 and lasting approximately one minute in duration, were recordings of stunts performed in Cody’s Wild West Show. Later, in 1898, Edison recorded two equally short fictional scenes, Cripple Creek Bar-room and Poker at Dawson City. Arguably, it was with these two films that the Western genre was born. But it was not until The Great Train Robbery (1905) that anything approximating the classical form of the genre emerged. Produced at the Edison Manufacturing Company and written, directed, photographed, and edited by the studio’s production-head Edwin S. Porter, the film is today regarded as a landmark in early film narrative. Running just over twelve minutes (approximately 750-800 feet, or one reel), it detailed the train-robbery, escape, and subsequent comeuppance of a gang of outlaws. A familiar motif that reoccurs with stunning frequency throughout the genre was here fresh and groundbreaking. Employing editing techniques never before used, Porter created a film that proved influential on all subsequent dramatic films and set the ball rolling for what would prove to be America’s most enduring and potent of film genres.  Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest chronicles the attempts of an early pioneer to rescue his baby daughter from the clutches of an eagle. The success of The Great Train Robbery led to many direct ripoffs, among them The Great Bank Robbery, The Hold-up of the Rocky Mountain Express, and The Little Train Robbery (specific release dates unknown), which indicated a public fascination with, if not the West, crime and lawlessness. For Porter it was to mark his apotheosis as a filmmaker and overshadow another thirteen years of filmmaking. However, from his post-Train Robbery filmography, one other project deserves mention here. Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest (1907) chronicles the attempts of an early pioneer to rescue his baby daughter from the clutches of an eagle. Leaving the close-knit community of pioneers, the father (played by then-actor, D.W. Griffith) ventures off into the wilderness to retrieve his daughter from the eagle that snatched her away. Like Train Robbery, Eagle’s Next replayed a typical adventure from the frontier cannon. But if Train Robbery bespoke of the violent lawlessness of Western bandits, Eagle’s Nest portrayed a different antagonist -- the wilderness itself. Dwarfing the pioneers with its immensity, the wilderness would struggle against being tamed, offering as resistence impenetrable buttresses, parched deserts, blizzards, sand-storms, and a variety of wild inhabitants, from Indians to Mexicans to hostile animals.

Page 1 The Myth and Pre-History of the Silent Western Page 2 Prospecting: The Edison Co. and Edwin S. Porter Page 3 Trail-Blazing: Broncho Billy Anderson, the Genre's First Cowboy Page 4 Pioneering: Griffith, Ince and the Western as Art and Commerce Page 5 Frontiersman: William S. Hart and Western Realism Page 6 Showmanship: Fairbanks, Mix and Jazz Age Cowboy Page 7 Epic Mythmaking: Cruze and Ford and the End of the Silent Era Page 8 Conclusion

|